Topic: Sustainable & Renewable

We need to care where our timber products come from

Why do we love wood but hate forestry?

OPINION: Nick Steel

A colleague told me an interesting story recently. He was at a dinner party and the age-old question of “what do you do for a living” came up. Forestry was his answer to which typically, some in the room frowned. A short conversation about the merits of local forestry ensued and the conversation moved on.

A while later one of the people in that conversation announced that her long awaited Ikea table had finally arrived. He asked her if it bothered her that Ikea had been accused of using illegally sourced timber and that there was a chance that this purchase supported that?

Her response was merely more than a shrug and great disappointment that he had “ruined her moment”. It was clear that she was happy to be anti-forestry, yet her love of her new Ikea table overrode any desire to consider the ethics of that timber.

The fact is many people don’t care where their timber products come from.

What was the last timber or paper/cardboard product that you bought? Was it imported from deforested land or was it from sustainable regenerated forests?

It’s a question we need to be asking, as addressing climate change is dependent on both stopping deforestation and reducing emissions.

The clear message from the Paris Agreement and the United Nations IPCC report is that carbon neutral isn’t enough – carbon negative must be achieved.

Yet the climate benefits of production forests are increasingly being challenged and used as a weapon by some in the environmental movement, leading to confusion and doubt as to the role for forestry in climate change mitigation.

But it gets worse, Dr Craig Brown recently wrote (Mercury 28 April) that an aluminium smelter driven by hydro electricity has “very low embodied carbon”. The case was to somehow suggest that aluminium has better environmental credentials than timber.

Greens senator Peter Wish-Wilson recently tweeted about the merits of green steel. Well Senator you don’t have to put “green” in front of forestry, as we are already there.

So toxic is the “anything but forestry” mantra that environmentalists are now arguing that non renewables are a viable replacement to carbon storing timber.

I think we all agree that meeting the challenges ahead is going to be hard and will require a substantial amount of carbon dioxide removal from the atmosphere, in conjunction with deep reductions in emissions.

The most prominent removal strategy in global modelling is afforestation/reforestation.

But afforestation initiatives for climate change mitigation commonly promote the establishment of conservation forests only, rather than production forests.

Production forests can provide climate change mitigation and emissions reduction through displacement of carbon-intensive building products.

Studies, such as the ones done by Fabiano Ximenes, Senior Research Scientist at the NSW Dept. of Primary Industries show that managed production forests deliver greater climate benefit than unharvested conservation forests, and the benefits compound over sequential harvests.

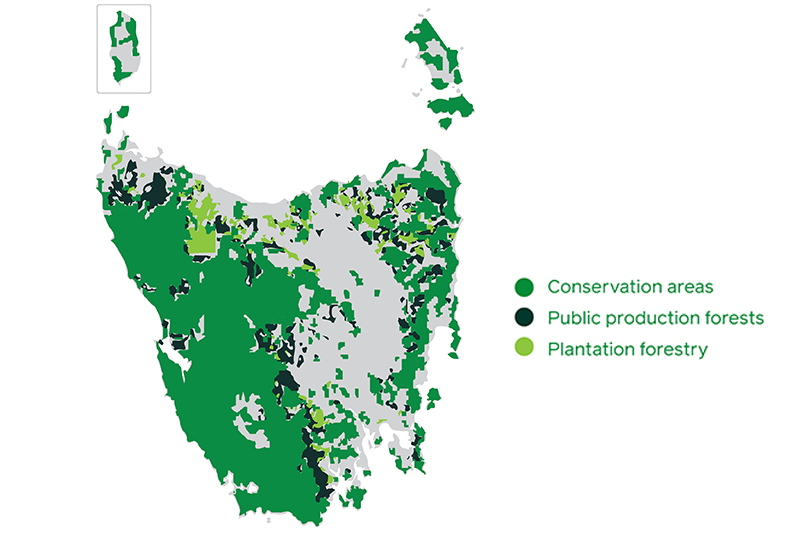

Of course, this isn’t to say we shouldn’t value our reserved forests, as around 50% of the state is reserved forests, but it is to say that the climate benefits of production forests, which are increasingly being challenged by the anti-forestry cause, need to be front and centre in any genuine conversation about climate change mitigation.

The argument that reserved forests alone are a silver bullet is flawed. The carbon sequestration potential in forests is finite and conservation forests are at best carbon neutral, as once forests reach maturity, the rate of sequestration slows until an equilibrium is reached.

Carbon sequestration and storage in forest products from managed forests is infinite and achieves the goals of being carbon negative by delivering both removal and storage of carbon from the atmosphere and reducing reliance on high emitting materials.

In addition, we know that we need to ensure the security of our domestic timber supply, the current shortages in the building industry have taught us that, but it goes much further than that.

We have a responsibility to grow timber.

Failure to produce these products domestically will lead to greater pressure on international markets, and potentially shift demand to regions where unsustainable forest management adversely impacts climate and biodiversity.

Timber shortages are a global issue and there is currently not enough timber to supply the world’s needs.

We have a responsibility as a global citizen to grow and harvest our fair share of timber, to do our share of the heavy lifting and produce at least enough forest products for our own domestic needs, if not more.

All countries that can produce sustainable forestry share this responsibility. It’s not acceptable that we would push this responsibility to countries where deforestation is rife and conversion from forest to pastures common practice.

Despite attempts by some to dismiss the reality of what forestry looks like in Borneo or the Amazon, shortages create demand and high demand can result in poor practices and illegal forestry which goes against all the principles of climate change mitigation.

I told the story at the start because we need to think about and care where our timber comes from.

This is important because the need for production forests globally is going to increase as we decarbonise the economy and those production forests need to remain as working forest.

We all love wood, so let’s start recognising and loving responsible and renewable forestry so we can continue to produce wood that we are proud of.

Nick Steel, CEO, Tasmanian Forest Products Association